Inca Warfare: Battle Tactics

This article is part of the Inca History of Peru series.

At its height, the Inca civilization could amass armies of sufficient size and strength to force rival civilizations into submission — or assimilation — without engaging in open battle. While forcing a surrender through a simple show of military strength was a preferred form of “diplomacy,” the Incas certainly didn’t shy away from open warfare when deemed necessary. When their pre-Columbian rivals were less than compliant, the disciplined forces of the Inca Empire would readily demonstrate their superiority on the battlefield.

Inca Warfare and a Show of Strength and Order

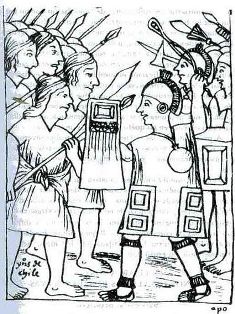

An Inca army (right) faces off against Chilean indians (Guamán Poma de Ayala)

The Inca war machine benefitted greatly from effective road and communication networks, as well as strategically placed storehouses (tambos). An Inca army marching from Cusco could swell its ranks on the move by calling on the militias of outlying settlements. The tambos, meanwhile, allowed a commander to keep his troops fed and in good fighting form during even the longest marches, with his men eventually taking to the field in relatively fresh condition and ready for battle.

The Sapa Inca (Inca ruler), therefore, could deploy his armies swiftly and efficiently to counter threats and expand the boundaries of the ever-growing empire.

At the end of a march and with the enemy nearby, the Incas would sometimes choose to discourage a rival army from engaging through a sheer show of superior force. According to Terence Wise, “The size of an Inca army depended entirely on the campaign to be undertaken, and strengths from 70,000 to 250,000 warriors are recorded.”

Such numbers, even at the lower end of the scale, could pose an insurmountable challenge to lesser civilizations. If submission could be achieved without the need for battle, the Inca commander would often accept a diplomatic surrender, absorbing rival tribes into the empire without resorting to open warfare. The price of later treachery, however, would likely be bloody and relentless.

Inca Tactics on the Battlefield

When the enemy chose to stubbornly stand its ground, the Inca army would set its battlefield tactics in motion. Typically, the pre-battle maneuvering would involve a psychological element designed to apply further pressure on the will of the enemy ranks.

As an unsettling display of discipline, Inca armies would customarily approach the field of battle in silence. Troop maneuvers and military parades would then commence as a further show of order and ability. Once in place, it was typical for both armies to begin an exchange of songs, insults, taunts and general posturing. If the enemy forces still stood firm, the commanding general (sometimes the Sapa Inca himself) would signal the attack.

Inca tactics in open battle followed a basic yet effective strategy, and one that can be seen throughout the history of warfare (the absence of mounted troops also served to limit the available tactical options). Inca formations typically consisted of weapon-specific units, often containing certain tribal or regional warriors adept in the use of one particular type of Inca weapon.

Standard attacks in open battle would commence with long-range units (such as slingers, archers and spear throwers) peppering enemy lines with projectile weapons. Following this initial softening of the enemy formations, the Inca commander would signal a full-frontal charge by the Inca shock troops. Wielding maces, clubs and battle-axes, these troops would engage directly with the front line of the enemy formation. If the enemy didn’t break, the two front lines would remain locked in a battle of attrition. Inca spearmen would join the fray in order to help hold the line of battle.

With hand-to-hand combat initiated, the Inca general would look to expose the enemy flanks (not unlike the classic “horns of the bull” formation). Generally, one third of the main body of the army would commit to the head-on assault with another third moving to attack both flanks; the rest would be held in reserve.

While the frontal attacks were less than subtle, Inca generals demonstrated greater flair with their flanking maneuvers. As historian Terence N. D’Altroy notes, feigned withdrawals and pincer counterattacks were favored techniques for wrapping up the enemy: “Both approaches indicate that the Incas used surprise to their advantage and concentrated force on the vulnerable flanks and rear of forces.”

Discipline was vital to the success of these maneuvers. Unlike many of their adversaries, Inca warriors would rarely break formation, allowing for greater control and manipulation of the battlefield.

Incas Armies Versus the Spanish Conquistadors

These open battle tactics, combined with an overreliance upon sheer numbers alone, would not fare well against the armies of the Spanish Conquistadors. Inca tactics versus the Conquistadors showed a fatal lack of adaptability, and an even more lethal vulnerability to cavalry charges.

While the armies of the Inca Empire had certainly shown themselves to be a disciplined and highly capable fighting force, the Spanish were more advanced technologically — and far more ruthless.

The arrival of the Spanish Conquistadors posed a new tactical problem to the mighty Inca Empire. While the overall impact of Conquistador weaponry and mounted units is sometimes overstated (they did, after all, begin their campaign against the Inca with only a little more than 100 infantry and 62 horses), standard Inca battle formations proved highly susceptible to cavalry charges.

Inca warriors would often find themselves fighting Spanish armies that consisted largely of familiar tribal enemies — native rivals now sided with the foreign invaders. At the Battle of Ollantaytambo, for example, Hernando Pizarro commanded about 100 Spaniards — 30 infantry, 70 cavalry — alongside an estimated 30,000 native allies. The Spanish units, however, could deliver shock attacks the likes of which the Incas had never seen. Tactically, and although small in number, Spanish infantry and cavalry could both be used to strike decisively when and where needed.

Cavalry units, in particular, gave the Spanish far greater mobility on the battlefield. Mounted units could be used to both rapidly counter standard Inca flanking maneuvers and launch vicious attacks of their own against the Inca flanks and rear. Even after the psychological impact of horses had lost much of its force, it was still all too clear that the Incas would have to adapt to this new mounted threat.

According to military historian Ian Heath, “the arrival of the Spaniards resulted in tactical changes, but these were largely of a defensive nature prompted by the effectiveness of Spanish cavalry.” It soon became clear to the Incas that defensive measures were needed in order to counter Spanish cavalry, especially in open terrain. The Incas turned to two tactical ploys: fighting in terrain that would naturally restrict the effectiveness of horses, or altering the terrain in order to impede them.

Whenever possible, Inca armies would fight battles and skirmishes in restrictive terrain such as mountain passes (such as the ambush at Vilcaconga), wetlands and jungle, all of which naturally limited the effectiveness of mounted troops. Tactical usage of narrow defiles also proved a successful strategy; Inca warriors would allow or entice the Spaniards to enter a narrow pass before attacking them from above with boulders, slings and arrows.

Where battle in open terrain was unavoidable, the Incas dug large holes filled with sharpened stakes. They would then lure cavalry toward these pits, which were covered with earth and vegetation; if the horse fell into the trap, both animal and rider would be impaled. If time or terrain did not allow for such large constructions, the Incas would dig smaller holes with the intention of tripping the horse and bringing down its rider.

Pizarro and his men charge at Atahualpa and his commanders.

A Fatal Lack of Adaptability?

Despite the need for new counter measures against the Conquistadors, the Incas did not adapt their battlefield tactics quickly enough to fend off this foreign threat. While there were notable and often heroic Inca victories in battle against the Spaniards, winning the war was a different prospect.

Terence N. D’Altroy highlights some key elements inherent within Inca warfare that served to hinder their defense against the Spanish: “the concentration of massed force, the physical leadership of the army by its officers, the three-pronged attack, and the collapse of the army’s discipline with the loss of its command.”

The Spanish, once aware of the Inca battle strategies, would always look to take down the commanding officer of any Inca force (at the Battle of Cajamarca, Pizarro and his men rode straight for Atahualpa and his top commanders). They knew that the fall of the commander could quickly turn the tide of battle; Inca warriors were disciplined, but would often break and run without leadership. The Inca overreliance on massed force would exacerbate the problem, turning rushed retreats into a bloodbath as the Spanish horsemen cut down the fleeing Incas.

Despite having skilled spear units within their ranks — with spears as long as 20 feet by some accounts — the Incas did not learn to use these weapons effectively against Conquistador horsemen. The Araucanian Indians (Mapuche) in Chile, for example, used spear walls to great effect against Spanish cavalry, but the Inca military did not utilize such methods successfully against mounted units.

While many other factors obviously worked against the Incas in their struggle against the Conquistadors (disease and the ensuing civil war, most notably), a lack of adaptability in traditional Inca warfare did not help defend against this new and brutal enemy.

ENTERTAINMENT TIP: If looking for fun at night, or to watch sports during the day, or even a taste of home, visit the Wild Rover Hostels Chain for great food, sports and beer! Entrance to their bars is free even for non-guests

7 comments for “Inca Warfare: Battle Tactics”