Chavín de Huantar

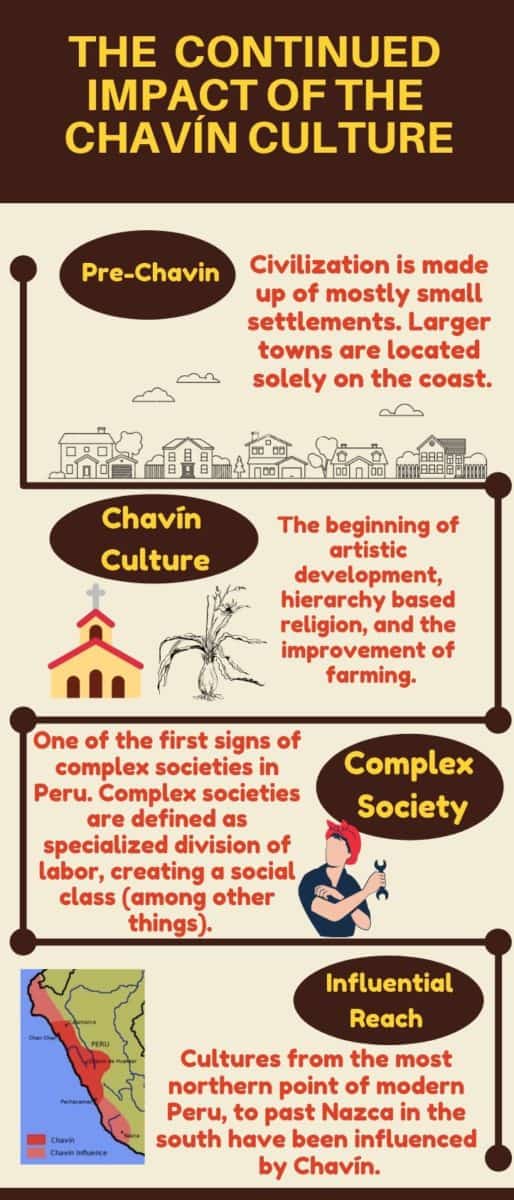

Experience the very beginnings of Peruvian culture as we know it. Chavín de Huantar holds the secrets to modern Peruvian art, religion and society. Arrival at the site may at first seem similar to any other archaeological spot, but wait until you get inside the temple. Find your way around the complex underground maze, as a historian explains exactly why these stones built the societies that we know today.

The ruins of Chavín de Huantar hold one of the first displays of art in all of Peru. Andean art has been forever influenced by the people who lived and worshiped on this sacred land. The temple here also shows the first signs of many artistic and architectural themes that become dominant in Andean cultures later in Peru. (The first being Caral: near to the coast). Chavín de Huantar has a plaza that held up to 1500 people in the center of its architectural layout.

Located in a valley nestled in the mountains, this is a place to truly appreciate Peruvian history. Explore the artworks and the complex buildings, marvel at the history, and, in the rainy season, listen to the noise of the jaguar roaring through the drainage system of the underground temple, which forms a complex maze in an amazing feat of engineering. A great alternative to Machu Picchu, don’t miss Chavín off your list of things to do in Peru.

The site was discovered by the father of Peruvian archaeology, Julio C. Tello. Tello theorized that Chavín represented the common root of larger Andean societies after smaller groups descended from the jungle in order to find more hospitable living conditions.

History of Chavín de Huantar

The site of Chavín de Huantar is unique; close to two rivers and a mountain valley, it is assumed to be situated where it is because of the ease of growing potatoes in the higher lands, and quinoa in the lower lands. Research suggests that this is what the majority of the diet of those who resided there was made up of. The site was active from around 900 BCE, with few residents or visiting worshipers, to around the third century CE. AroThe height of the cult’s influence was around 500 BCE, which is when ‘the new temple’ was built, allowing more space for followers. Reasons for the abandonment of the site are unclear, but it is assumed that several years of earthquakes and drought caused social upheaval and the eventual abandonment of the religious site.

The people of Chavín had no official form of writing, and since the site was abandoned until the Spanish happened across the ruins in 1616, very little is known for sure about it. It is a registered UNESCO world heritage site, and has been listed as such since 1985, after being recognized as a dividing line between basic monuments and complex structures and worldviews that would later arrive to major civilizations in Peru.

The Religion of Chavín de Huantar

The archaeological site is most definitely a site of religious importance, but as the people had no writings, we can only derive so much. Because of this, the name of the religious cult is not known. Consequently it has been named as ‘Chavín’ after the land it rests on. It is known that the site was the main culture point for the early horizon period in the highlands of Peru. It was recognized for the intense religious cult, the improvement of farming (as opposed to hunter/gatherer), and its pivotal art and ceramic work.

The religion of Chavín holds interest not only for its age and artistic influence, but also as it shows signs of religious pilgrimages. This is an incredible feat for such early times; signs of pilgrimages have been found from as early as 500 BCE. The writer Vasquez de Espinoza offered this assessment of the cultural site: “It was a huaca or sanctuary, one of the most famous of the gentiles, like Rome or Jerusalem among us; a place where the Indians came to make offerings and sacrifices, because the demon in this place declared many oracles to them, and so they attended from throughout the kingdom”. Monkey bones (from the jungle) have been found alongside conch shells (from the coast) within the ruins. The conch shells had holes drilled into them and were likely used as trumpets to create music during ceremonies. Along with singers chanting and incense being burnt, this paints a magnificent picture of the sort of sensory stimulation that occurred during ceremonial events.

Secret staircases have been found to different levels of the temple from the platform, allowing Shaman to disappear and seemingly appear at different heights and levels of the temple during ceremonies. This is not the only architectural feat the would have contributed to the energy of the temple and ceremonies. Thanks to its position in the highlands, the rainy season would have had the potential to affect religious life in a negative way. However, the Chavín temple had a very advanced drainage system, and an advanced understanding of acoustics. As a consequence, the drainage system running under the temple created a noise similar to a jaguar’s roar while the rains fell. All of these different experienced played into the illusion of magic during the services.

Artwork found at the site suggests heavy and regular usage of psychoactive plants, most notably the mescaline cactus, San Pedro. The religion was led by an elite group of Shaman, who regularly drank the psychoactive substance from the plant, or other similar psychoactive materials, in order to enter a psychoactive trance. While in this trance, they would seemingly connect with the gods. The religious ceremonies of the Chavín cult were multi-sensory events, with the music, the illusions of magic, and often blood offerings and sacrificial rituals. These would be performed either inside the temple (in a private ceremony) or above it, and viewed from the grand plaza.

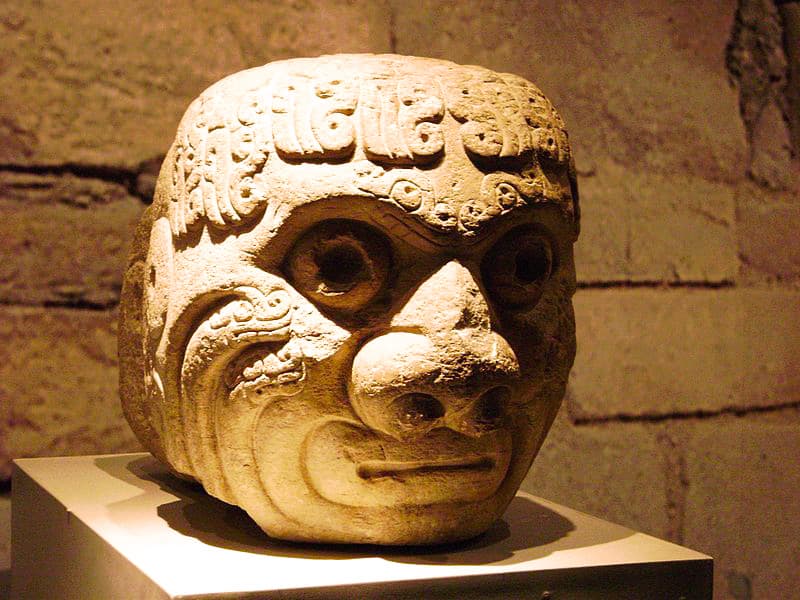

It is highly suspected that the only people allowed inside the temple would have been the Shamans in charge. This is understood by the increasing complexity of the carvings and the artwork inside the temple (see Artistic Influence section). Made up of a series of long underground tunnels, the eventual total length of these channels is over two kilometers. Right at the center of this maze you will find the lazón. The lazón, named after the Spanish word for lance (after its shape), is a deity carved into a 4.5 meter tall granite pillar. When sketched flat it shows an impressive yet intimidating face. It is thought that worshipers would be led through the pitch black tunnels after taking the psychoactive plant, before eventually coming across the huge intimidating face bathed in light.

Further Influence of the Chavín Religion

Chavín de Huantar represents a paradigm shift in Peruvian life. Until this point, more complex societies lived on the coast. With Chavín, this shifted daily life to the highlands. With more fertile land and better access to fresh water, life in highland Peru became the norm. The beliefs and even the structure of the Chavín religion were passed on through generations, influencing even until today: a hierarchy, an elite class specifically for priests, and followers who relied on the elite to contact the gods on their behalf. All of this originated with Chavín, and spread not only through the Andean cultures, but back to the coastal area as well, eventually becoming the norm of Peru.

Artistic Influence

Much of the art of the Chavín has religious and sacred significance. The notable iconography of the cult was based off Andean artwork, and influenced artwork all over Peru. Similar emblems have been found in many religious societies since, in both coastal and in Andean societies. The artwork here was pivotal to the future of Andean art. The complexity of the work, and the use of it to tell stories and keep notes is in abstract form, intentionally difficult to understand. This is so that the high priests, or shaman, are the only ones who may understand the sacred designs. The most common figures of this artwork are jaguars and eagles, unusual for the location as neither of these animals are native to the area.

A major part of the artistic influence of Chavín is in the stonework in the temple. Giant stone heads protrude from the walls, with human and jaguar features, stone carvings decorating the interior of the temple. The people of Chavín also showed a great deal of expertise in metalwork. There is gold that has been worked in an advanced way, and even evidence of soldering (using heated metal to fuse other metals together).

Getting to Chavín de Huantar

The access point to get to Chavín de Huantar is from the town of Huaraz. To get to Huaraz from Lima, you simply need to catch a bus from any of the larger bus stations, either in Plaza Norte, or in La Victoria. Once you are in Huaraz, you have two options for getting to Chavín de Huantar. For viewing this site, it is advisable to take a tour so as to fully understand and appreciate the significance of each section of the site, and for the transport there. It is a three hour drive from Huaraz to the town next to Chavín. From there you will walk to the ruins. A tour will cost you roughly $15 booked from Huaraz, and includes the entrance fee and guide.

It is also possible to include this site on a three day Inca trail segment between Olleros in Southern Huaraz and the town of Chavín. To do this it is absolutely necessary for you to hire a local guide.

Perhaps the reason why Chavín was so influential was that it was in the center of trading routes between the Andes and the coast. This could also be why the technology they used was so advanced: its location allowed it to soak up information from all over Peru. At its peak influence, evidence has been found to reach as far as Paracas on the coast and Pukara in the southern highlands.

This is a site that marks a pivotal change in everything that is understood about Andean life, Andean art and architecture. Every site that you visit of Peru’s rich history has roots in these grounds. If you wish to truly understand something, you must start at the very beginning. Chavín de Huantar is that beginning.